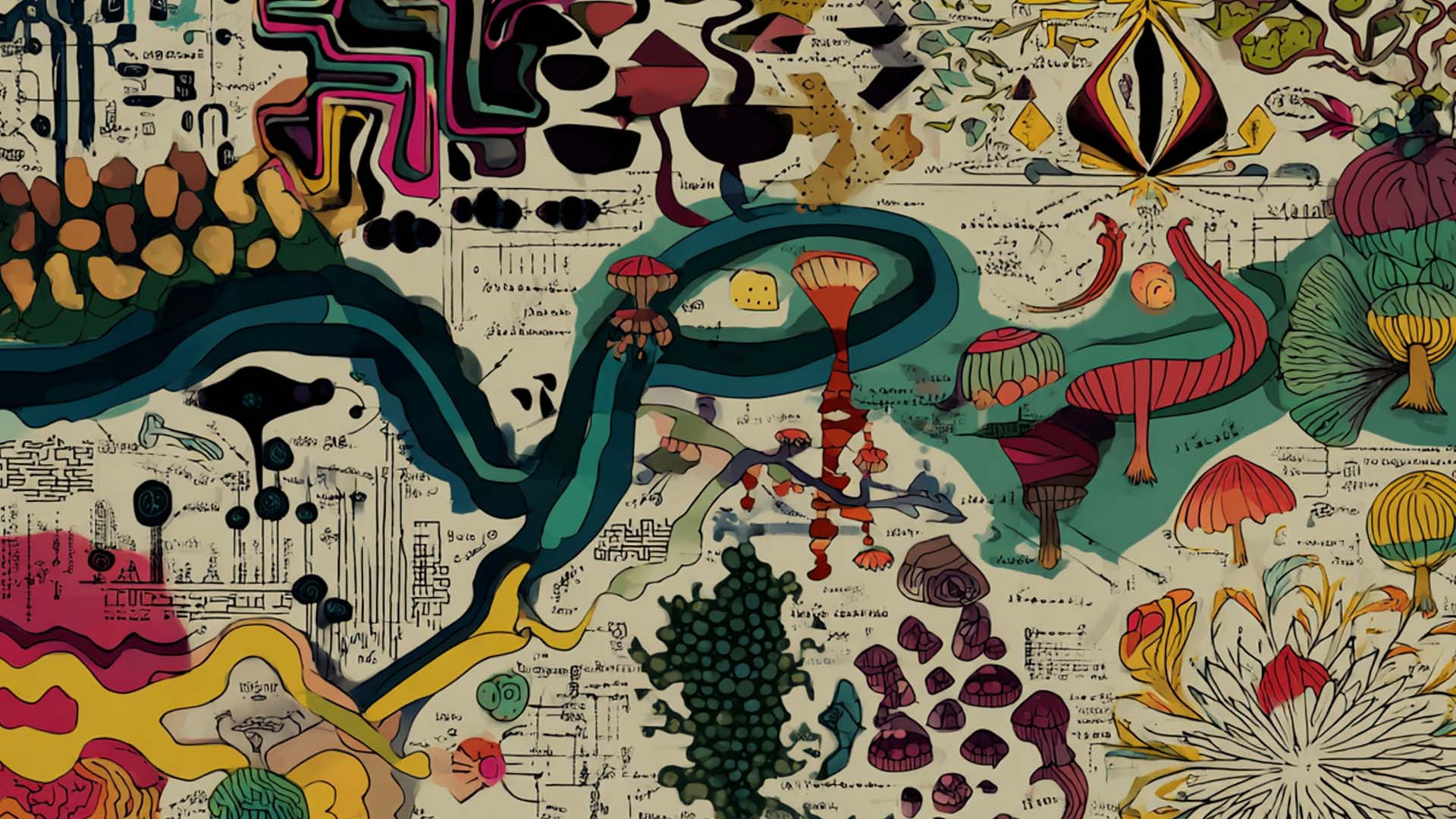

Art as an Ecosystem: Creativity, Design, and Sustainability

Art as an Ecosystem: Creativity, Design, and Sustainability

The greatest challenges we face today—such as climate change and social inequality—have accelerated in part as a result of technological development and the overexploitation of natural resources, both stemming from a technocratic worldview and a consumer-driven way of life. Art serves as a catalyst: in many cases, it provides a social thermometer that allows us to understand the state of health of society and the environment. Yet its role does not end at naming or revealing these issues; it also anticipates possible pathways and outcomes resulting from our contemporary modes of development.

Movements such as Land Art, Arte Povera, and Junk Art have taken a critical stance toward the human impact on the environment, integrating actions rooted in ecological awareness¹. One of the pioneering artists in this field is Alan Sonfist, whose work Time Landscape is considered one of the first ecological urban sculptures. The project—located at the corner of LaGuardia Place and Houston Street in New York—consisted of reconstructing a micro-forest using native species, replicating the landscape as it might have appeared in the 17th century². Sonfist collaborated with local communities, researchers, and municipal authorities to recreate three stages of forest growth, thus creating a “living monument” to the ecological memory of the site³. With this work, art redefines the concepts of sculpture, urban planning, and landscape design; it encourages respect for the environment and places nature at the center. It becomes a form of regeneration rather than a negative-impact aesthetic intervention. Land Art and related practices form early foundations of sustainable thinking in art⁴. At the same time, eco-art and expressions that use recycled materials—such as Junk Art—expand this awareness, inviting reflection, action, and habit transformation. Art integrated into the environment, understood as a living space, helps us recognize that the environment we breathe, move through, and inhabit is a shared resource. In this sense, design and architecture also contribute to imagining sustainable models.

Designers such as Marjan van Aubel and Pauline van Dongen have worked on solar-energy-based proposals while questioning the post-use impact of technologies such as solar panels⁵. Another example of the interplay between art, science, and sustainability is the work of architect and inventor Bob Hendrikx, who developed the ecological coffin Living Cocoon, made from mycelium and biodegradable fibers. It allows the body to decompose naturally and reduces the environmental footprint of traditional funerary rituals⁶. Global warming, the overexploitation of natural resources, and the rise of social inequalities require creativity, knowledge, and practical solutions that arise from an awareness of the future—toward sustainable lifestyles that respect our habitat and the environment.

Art also acts as a driver of social awareness, appealing to emotion and transforming abstract concepts into real, tangible experiences through metaphor. A clear example is the work Ice Watch by Norwegian-Danish artist Olafur Eliasson, who placed large blocks of glacial ice in public spaces so that viewers could witness their gradual melting, making the effects of climate change palpable⁷.