Food to value

The Challenge

Organic waste is one of the most pressing pain points in modern waste systems. Households generate the majority of food waste, inflating collection costs, and contributing to the emission of Greenhouse gases (GHG) as methane during decomposition of the waste in the overloading landfills, and releasing methane. Legacy systems were designed to remove waste, not to valorize it. In dense urban areas, transporting wet, low-density material over long distances is expensive and emissions-intensive.

Meanwhile, policies are evolving: more jurisdictions are mandating source separation for bio-waste.

The Challenge

Organic waste is one of the most pressing pain points in modern waste systems. Households generate the majority of food waste, inflating collection costs, and contributing to the emission of Greenhouse gases (GHG) as methane during decomposition of the waste in the overloading landfills, and releasing methane. Legacy systems were designed to remove waste, not to valorize it. In dense urban areas, transporting wet, low-density material over long distances is expensive and emissions-intensive.

Meanwhile, policies are evolving: more jurisdictions are mandating source separation for bio-waste.

(1) K aza, S ilpa et al, W hat a W aste 2.0: A Global S napshot of S olid W aste Management to 2050 . U rban D evelopment, © W ashington, DC : W orld B ank, 2018

(

2) Christian, Riuji Lohri et at, Treatment technologies for urban solid biowaste to create value products: a review with focus on low- and middle-income setti ngs, Reviews on environmental science and bio /

technology, 2017

(3) Eurostat, W aste Generation in Europe – excluding mineral waste , S eptember 2024

(4) Bénédicte, B akan et al, Circular Economy A pplied to Organic Residues and W astewater: Research Challenges, W aste and B iomass V alorization, 2021

(5) Pooja, S harma et al, S ustainable Organic W aste Management and F uture D irections for Environmental Protection and Techno-Economic Perspectives, C urrent Pollution Reports, 2024

This reduces contamination and enables higher-value applications —but only if paired with accessible, community-operable technologies and clear market pathways. Our thesis: there is no single silver bullet. Real, scalable impact comes from a portfolio of solutions—biological, nature- inspired, and tech-driven— deployed closer to the source and supported by education, policy, and markets.

1) Biological Pathways

Composting

Composting is a natural process where food scraps and garden waste break down with the help of air and microbes, turning into a safe and useful material called compost. The heat produced during this process helps destroy harmful germs (6). Successful composting depends mainly on having the right mix of materials and enough air to keep the process healthy and odor-free. Adding a small amount of biochar can also make composting cleaner by reducing gas emissions and keeping more nutrients in the compost (7). It’s important to use clean, separated waste because mixing in regular trash can add small plastic particles; for this reason, sorting waste at the source and checking compost quality are essential (8).

Fermentation

Fermentation is the low-oxygen, microbe-driven conversion of organic waste into energy (biogas/biomethane) and building-block chemicals. For energy (anaerobic digestion), stable performance hinges on keeping ammonia, pH, temperature, and loading in safe ranges (9)(10). For chemicals, stopping earlier yields volatile fatty acids ( VFAs) that can be upgraded to higher-value products like caproate; the main cost hurdle is separation, where newer membrane/in-situ recovery systems are improving yields and economics (11)(12)

Fungal Decomposition

Uses oxygen-loving fungi to break down tough plant matter (woody, fibrous residues) by secreting powerful enzymes—laccase, manganese peroxidase, lignin peroxidase—that open up lignin and expose cellulose/hemicellulose (13)(14). Practically, it’s run as solid- state treatments on moist biomass to “pre-soften” straw, husks, etc., improving digestibility or downstream conversion (e.g., to biogas or feeds), with demo-scale results reported (15). Performance hinges on moisture/aeration and picking robust white-rot fungi; co-cultures and process tweaks are active levers to speed rates (16).

2) Nature-Inspired Innovation

Microbial Bioconversion

Uses tailored microbes (single strains or consortia) to turn organic wastes—food scraps, ag residues, even methane—into targeted products under controlled conditions (oxygen level, pH, temperature). This enables modular, circular production at small or industrial scale.Two proven plays: single-cell protein (SCP), where methanotrophs or other microbes convert methane/methanol into high-protein biomass for food/feed; recent reviews and pilots highlight fast growth and strong land/water efficiency (17).

For materials/chemicals, mixed-culture fermentation of food waste yields VFAs that are upgraded to bioplastics (PHAs) or higher-value MCCAs (e.g., caproate); viability hinges on matching feedstock ↔ microbe and efficient product recovery/separation (18).

Algal Cultivation

Grows microalgae in open ponds or closed photobioreactors (PBRs) to turn sunlight, CO₂ and nutrients—often from wastewater—into biomass rich in proteins, lipids and pigments for fuels, food/feed and specialty products(1). For economics, TEAs consistently show raceway ponds keep a cost edge for low-cost fuels, while PBRs justify higher CAPEX when targeting premium products or tighter quality control. Biggest hurdle: harvesting/dewatering—the energy/ cost hotspot—where recent reviews highlight hybrid and membrane- enabled approaches reducing unit costs. A practical upside is co- treating wastewater, which removes N/P while supplying nutrients and adding CO₂-capture co-benefits—several real plants and pilots report strong performance with algae–bacteria consortia.

Fungal Protein

Produced by cultivating filamentous fungi (e.g., Fusarium venenatum) in aerobic fermenters to turn clean, traceable food/agro side- streams into a complete, protein-rich mycelial biomass with a meat- like texture (19). In free-living randomized trials (~4 weeks), replacing meat with mycoprotein lowered total and LDL cholesterol (20). Independent reviews generally find lower greenhouse-gas footprints than beef, with outcomes sensitive to electricity mix and siting (21).

Historic side-stream pathways (e.g., PEKILO using Paecilomyces variotii on sulphite-liquor) show the waste-to-value feasibility for feed and inform modern deployments (17).

3) Tech-Driven Recovery

Anaerobic Digestion (AD)

Microbes break down organic waste without oxygen to make biogas (energy) and digestate (nutrients). In practice, reliable plants focus on avoiding free-ammonia inhibition by tuning pH, temperature, organic loading and retention time; mitigation ranges from microbiome management to emerging “weak electrical stimulation” strategies (22)(23). A pragmatic lever is biochar addition, which can buffer shocks and sometimes raise methane yield—benefits are feedstock- and dose-dependent (24). For markets, raw biogas is commonly upgraded to biomethane with compact polymer-membrane units that separate CO₂ efficiently (25). Downstream, struvite precipitation recovers phosphorus (and some nitrogen) from digestate into saleable fertilizers, cutting treatment loads.

Starch Extraction & Chemical Recovery

In the organic-waste space, this targets clean food/agro side-streams before they become effluent: physical separation (milling + hydrocyclones) captures native starch, enzyme-assisted steps unlock starch from fibrous residues, and UF→NF/RO trains recover fine starch/protein while returning reuse-quality water; closing the loop, CIP caustic can be regenerated via NF + membrane distillation, cutting chemicals and wastewater—delivering more sellable product per ton, lower COD/N loads, and tighter water/chemical cycles (26) Thermochemical Conversion (Pyrolysis, Gasification, Hydrothermal Liquefaction) Turns organic wastes into energy carriers and materials using heat instead of microbes. For dry feeds, pyrolysis makes bio-oil, biochar, and gas; product split depends on temperature/heating rate and reactor design (27). For wet feeds (e.g., sludge, food waste slurries), hydrothermal liquefaction (HTL) makes biocrude without costly drying (28). Gasification makes syngas for fuels/chemicals but requirestar control via temperature, residence time, and catalysis (29).

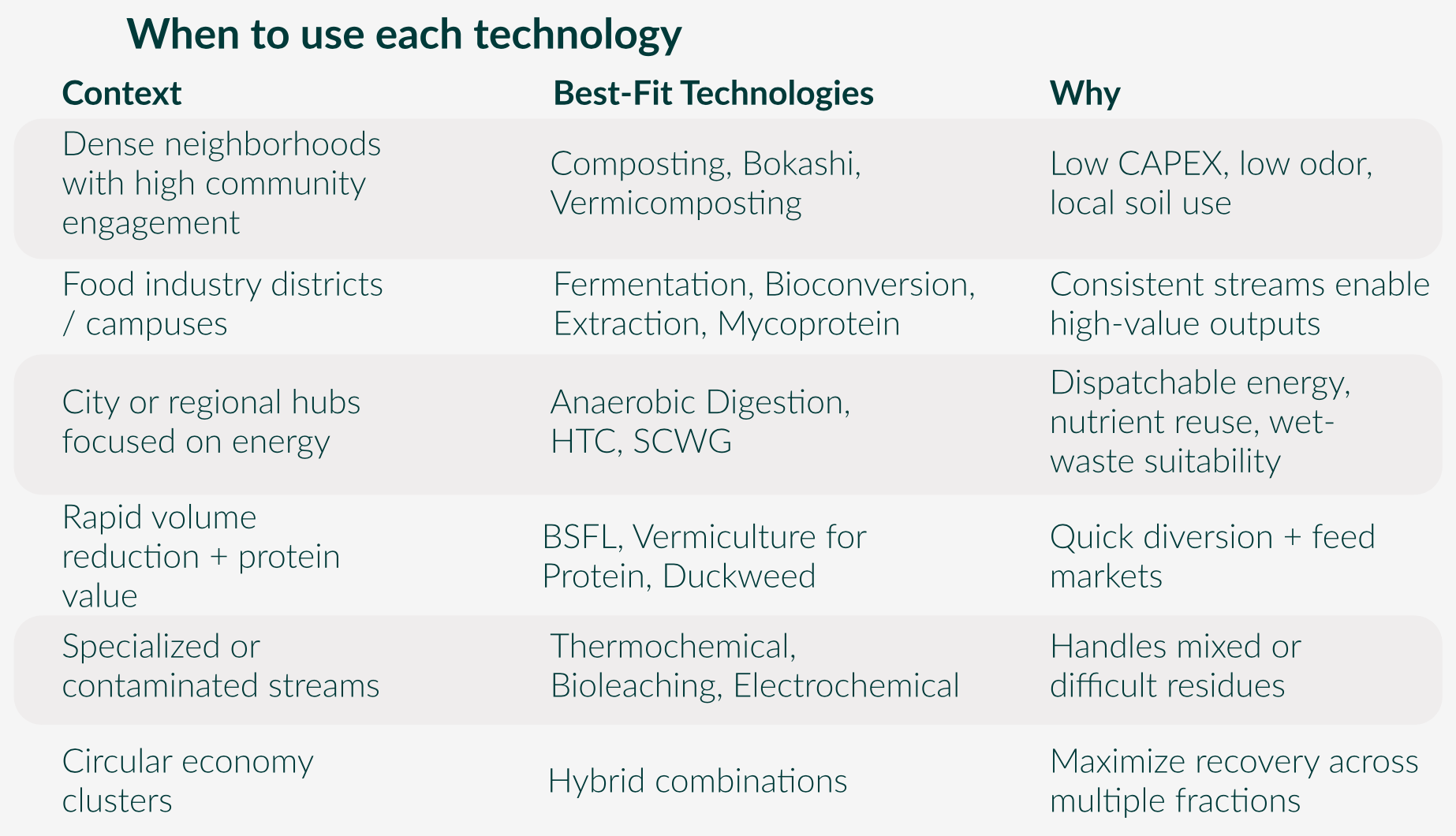

While these technologies align with specific contexts and objectives, their successful deployment depends on effectively managing operational, social, and market-related risks.

Risks & Mitigations

- Feedstock contamination: Education, simple bin design, and feedback loops.

- Odor & public acceptance: Enclosed or covered systems, biofilters, transparent site tours.

- Market volatility: Diversify outputs and secure anchor offtake early.

- CAPEX barriers: Start modular and decentralized, scaling up as data and participation grow.

- Regulatory uncertainty: Engage early with policymakers, align with evolving standards, and participate in industry coalitions to anticipate and shape future regulations.

Household organics are both the challenge and the gateway to a circular future.

With bio-waste segregation advancing, cities can move from disposal to resource conversion—producing local energy, soil fertility, and bio-based products while cutting emissions and costs.

While a wide spectrum of biological and technological pathways exists, some stand out for their current scalability and market traction. Fermentation, composting, fungal decomposition, algal cultivation, microbial bioconversion, fungal protein, starch and chemical extraction, anaerobic digestion, and thermochemical conversion together represent the segments capturing the largest share of the market today. Highlighting them does not mean they are the only valid solutions— rather, they illustrate where scale, infrastructure, and investment are already converging. Exploring these pathways in depth allows us to understand how each can be deployed, combined, and adapted to accelerate the transition toward a circular bioeconomy. In the coming weeks, we will publish deep-dive briefs on each of these technologies—covering, some of the barriers these technologies can face, small scale solutions, case studies, standout startups, active investors, and grant opportunities. No single pathway will solve the challenge alone; understanding their strengths, limits, and contexts is what unlocks scalable solutions. At the same time, it is important to note that this research only addresses one part of the broader circular ecosystem, where mobility, energy, food systems, and policy all interconnect.

If you’re a startup refining your strategy to scale, structuring your data room, or tackling manufacturing challenges—or an investor seeking technical diligence to de-risk a thesis or explore new spaces in the circular bioeconomy—we can help. Let’s connect to turn organic waste into local value.